The late February flurry could not do much damage. The falling flakes gave over to freezing drizzle in capitulation to the distant but oncoming spring, and the snow withdrew from the ground like a shadow at noon. When the next day dawned, driving conditions were not what any prudent Englishman would have called ‘navigable.’ But Newton Geiszler, Ph.D., was neither prudent nor—he was proud to say—was he an Englishman. On the morning of February 23rd, he rode his motorcycle to the office.

Division headquarters was decried by most of its employees as insecure. For the most secret office in the capital, its location was the city’s worst-kept secret. Ten years since the crisis, they said, and had we learned nothing? Vice Chief Victor had said that once, as an experiment, he got into a cab and asked for their headquarters. The cabbie took him straight there, asking only if he wanted to go in front or round the back.

This tradition was perfectly satisfactory to Newt. He parked his noisy American combustion engine in the underground garage per usual and walked the remaining blocks on foot. He climbed the concrete steps of the Century Building, greeted the front desk receptionist (to cheery reply), the morning watchman (to no reply), and pushed the button for a lift going down. His pressed colleagues had already pressed for the lift up. They gave him their usual curt greetings, and when their lift arrived first, they stepped in. The doors closed on Dr. Geiszler, hands in pockets, waiting for his ride down to the basement.

Everyone knew that the radio coding lab in the Century sub-basement was run by eccentrics. In the oblique language of the Division, they were known as “specialists,” but their nickname in mixed company was the “Looney Tuners.” Geiszler and his acerbic colleague Gottlieb, under operations manager Hal Weeks, ran radio technology and cryptography research. They developed new technology and techniques for signals interception and analysis. Newton Geiszler was an engineer, taking apart Soviet surveillance tech and building it better for the Division. Hermann Gottlieb was a cryptanalyst, analyzing enemy codes and writing ways of undoing them. These methods they passed upstairs, to ops and the coding bay respectively.

Upstairs, Weeks did his faltering best under the excessively watchful eye of Vice Chief Victor. (Victor was his only name—whether it was his Christian name or his surname was unknown.) It was he who had cleaned the Division out, top to bottom, after the crisis of 1963; but his paranoia had not stopped there. Over the next ten years it had grown. He prowled the halls and filing cabinets and databanks, sniffing out double agents where there were none. And he did it all with the tacit blessing of the unseen Chief, who had no name at all.

Geiszler and Gottlieb survived on their reputation as insufferable but effective. They were tolerated for their abilities and laughed at for their bickering. Colleagues speculated on whether they actually hated each other, but by and large, they thought not. Gottlieb and Geiszler looked out for each other the way people at the bottom do. And if any of their colleagues had discovered that they had keys to each other’s apartments on their respective keyrings, perhaps that would not have been a surprise.

Newt entered the door code and was admitted, with a beep, to the lab. All the desks were empty except for Dr. Gottlieb’s. His most punctual colleague was already hard at work.

He spared him an over-the-glasses glance. “You’ve survived another commute, I see.”

“I told you I would,” said Newt, setting down his bag and unbuttoning his jacket. “It’s a lucky day.”

“Is it?” said Hermann.

“Check your calendar, Doctorate in Mathematics,” Newt said. “The date is all primes.”

“My degree is in mathematics, not number trivia,” Hermann said, looking back at his dispatches.

“Of course. My apologies. Primes. So trivial. So rational. So concrete. Can’t have that.” Newt hung up his jacket. “I’ll come back when the date aligns with something nice and imaginary. Some abstract, abstruse equation that has no bearing on the real world.”

“You do that,” Hermann replied. “In any case, it’s 1973. There will be prime dates all year.”

“Exactly.” Newt picked up his bag and headed towards his office door. “So it’s going to be a very lucky year.”

“Superstitious,” Hermann called after him without looking up. “And irrational. Just like every year with you.”

But it was Dr. Geiszler’s optimistic superstition that bore out, because lying on his desk was a very special file. He opened it, and right away saw two things: one, that it contained a blueprint for a top secret new transmitter, and two, a that it was not for his eyes. This file was labeled fifth-floor only.

Newt ran out into the hall to see the receding back of the useless kid who’d delivered it. He called him back and handed him the file: “I don’t know whose desk this is supposed to be landing on, but it’s not mine. Don’t worry. I won’t tell them. Morning, Wesley,” he added to their labmate, who was just arriving. Wesley appeared not to hear. Newt returned to his office.

His employers knew that he was exceptional, perhaps even a genius in his field. They were lucky to have him in the Division at all, they said. By all rights, he should have been at the D.O.D. in his motherland. But what they did not know—what he had succeeded in concealing for nearly two decades—was that Dr. Geiszler had an eidetic memory.

One look at the blueprint was all he needed.

“I should like to write you the kind of words that burn the paper they are written on—but words like that have a way of being not only unforgettable but unforgivable. You will burn the paper in any case; and I would rather there should be nothing in it that you cannot forget if you want to.”

— Lord Peter Wimsey, Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night

1971

Two years earlier

The nurse had noted that morning that it would be particularly warm; she could tell from the way the clouds hung low and gray at dawn. Now sunlight rained down outside, and dark afternoon heat drenched the corridors in the hospital. Her mother used to call it die Affenhitze, the ‘ape heat.’ The nurse hadn’t heard that expression much since her childhood, but on such days, it resurfaced in her mind.

Krankenhaus Sankt Magnus stood on the furthest outskirts of East Berlin. It was a low series of brick buildings, secluded among the trees. She had worked there for the last fifteen years. Like any hospital in East Berlin, it was a public hospital, but somehow it seemed to have more money than most.

She wheeled her cart to the end of the main building, towards the long-term ward. She had finished her rounds, but then her supervisor, wiping the perspiration from his forehead, had asked, “Can you see to the long-term ward as well?” She’d obliged, hiding her reluctance. The long-term ward made her sad, and uneasy.

The ward was at the westernmost corner of the building, near the riverbank. The exterior walls were lined with windows, but all the blinds were drawn, and so were the gauzy inner curtains. It gave the clean white ward that special darkness found only in shaded spaces shielded from harsh sunlight.

Before her lay a dozen pale, motionless bodies. She slowly pushed her cart along the aisle between their two rows. The long-term coma patients were so few that they felt like a community—like they played cards together on weekends, smoking and talking of the old days. But they were drained as white as the rooms around them, and they slept as if they were already dead.

She stopped at the end of the row beside the windows. The last man in the ward had deep lines under his eyes and between his thick red brows. His leathery skin looked like it had survived deep sunburns in far more tropical places than this. He was not as pale as the others—in fact, his face was a bit ruddy. It seemed he was the only one who felt the heat. Sweat beaded around his peaked hairline.

The nurse remembered his arrival, almost nine years before. They knew nothing of him. He had arrived anonymously. They had removed the bullet in his chest and treated his burns, but he had not awoken. His external wounds had long since healed; there remained something internal that would not resolve.

Yet he sweated. The nurse tsked softly and went to the window. She pulled up the blinds and sunlight poured in.

She turned back to the sweating man. His eyes were open.

She gasped and jumped back, grabbing the headboard behind her.

He opened his mouth, forming a word: “Gott... Gott...”

Trembling, she laid her hand on his shoulder.

“Water,” he croaked at last.

Why had he switched to English? The nurse recovered herself enough to nod.

She moved towards the sink, but a hand caught her wrist. His grip was impossibly firm for a man in his condition.

“Wait.”

“Sir,” she said, speaking German, for though she understood some English, she could not speak it. “Please let go. You need water. I need to call the doctor.”

“No, no doctor,” he said, switching back to German. His accent was flawless. “I need the embassy.”

“You need a doctor.”

“I need the embassy.”

“Which embassy?” she said. “You are a diplomat, sir?”

He coughed. His lined, ruddy face was sweating more than ever, but his voice was bone dry. She had never seen anyone who looked less like a diplomat.

“What year is it?”

She shivered.

“Sir... You must let me call the doctor.”

He squeezed her wrist. With his brown eyes open he looked years younger already. They begged her ear, made her complicit. “Call no one. Please. Tell me. What year is this?”

“1971.”

The man relaxed slowly, eyes sliding away. The lines of his face loosened from consternation into something more obscure.

“Let me get you water,” she said softly.

He let go of her arm.

The nurse hurried to the ward phone and called the dispatch desk. But the internal line was busy. Agitated, she told him that she would return and to please lie still. He nodded wordlessly. His eyes were on the phone.

It took her five minutes to get to the dispatch desk. The nurse on duty did not know where to find the right doctor, and they spent ten minutes looking for him. But he was busy, and could not come until he had finished his consultation, and by the time he finally did, almost half an hour had passed. The nurse was agitated—the man’s wild eyes and strong grip had left an impression of danger. Whether he was in it, or was it, she did not know. But she did not like to leave him alone.

When she finally herded the doctor, her supervisor, and another nurse back to the ward, the man was gone. His bed was empty. The phone was off the hook. The window was open.

It was impossible that he had walked, after eight years spent dead. Impossible, the doctor said. His muscles would be completely atrophied. He must have had help. So who then, the supervisor asked, who took him? Who did he call?

They said it was impossible—yet the nurse’s instincts said otherwise. None of them had felt that grip.

The window was still open, the same window whose blinds she had raised to let in the light. No breeze disturbed the translucent curtain.

31 May, 1973

Thursday

It was Hermann Gottlieb’s belief that as long as he continued to behave as normal, any out-of-the-ordinary situation would resolve itself. If something was amiss in the system, it was because somebody else had done something untoward. The usual suspects were foreign agents, retail clerks, small committees high up in national government, and his partner. But none were any match for Hermann’s routine, and the doggedness with which he could stick to it.

So on this Thursday he left the Century Building at 5 PM, as if it were a normal weekday evening. There were several reasons why it was not.

“Vice Chief Victor believes there is a mole among us.”

The words echoed in his mind as he descended the Lambeth North staircase with the crowd. Those words had been spoken in Weeks’s office a few hours before, and they would have impressed Hermann more if he hadn’t heard them every few months since the crisis of 1963.

The train arrived crowded and Hermann boarded it with everyone else. All the seats were occupied by the time he got on, and only one person looked up. The stranger’s eyes flicked up to Dr. Gottlieb’s cane, up to his bent middle, and then to his face. He bestowed upon Hermann an openly hostile look before reopening his newspaper. Hermann’s face twitched angrily, and since he was distracted when the train started to move, he stumbled sideways. He bumped into an older woman in an overcoat, who steadied him and asked if he was all right.

“Quite,” he snapped, taking hold of a pole.

The woman turning away in a huff would have been astonished to learn that the man spreading waves of irritation throughout the subway car was a valuable asset to British intelligence. Hermann Gottlieb was a tallish, thinnish man with a cane and a vague continental anonymity. He was professorially dressed and professorially hunched. His face was strangely geometric, like it had been sculpted by an art student who only had access to sharp-angled tools. If you asked his family, he worked for the Treasury. His neighbors were aware that he worked for ‘the government.’ A stranger would have taken him for an accountant, a teacher, or a mathematician. The former was true, if you asked his labmate; the latter was true if you asked his bosses. Hermann was one of the foremost minds in British cryptanalysis, and had been for almost twenty years.

“We—” Weeks had stumbled on the pronoun, eyes darting sideways to where Victor’s menacing assistant stood in the corner, out of his eyeline—“We, uh, believe Orpheus is a serious threat. We’re upgrading him to top priority.”

Weeks had called Gottlieb into his office that afternoon to nervously relay this message, courtesy of Victor’s assistant Preston Blair, a pint-sized bulldog in a well-fitted suit. It seemed the further Vice Chief Victor retreated into his files, the more Hermann saw of Preston, and the further Victor’s reach grew in the service. In fact, he didn’t think he had seen Victor once since the new year. He was becoming as reclusive as the Chief.

“Top priority, sir?” Hermann shot Preston a suspicious glance. “We’ve been picking up these Orpheus transmissions for nearly two years.”

The train jerked, and Herman winced as his back bent with the effort of staying on his feet. He straightened up, sighing through his nose. He did not look down at the people sitting placidly in their seats, and they did not look up at him. Though born in Germany, he had long assimilated into the codes of English discourtesy. He put his free hand on his hip and tried to keep it still. It was beginning to ache insistently.

The Orpheus transmissions had started appearing at irregular and intense intervals in radio traffic two years ago. Among hundreds of routine Razvedka signals sent from fixed positions, Orpheus broadcast at irregular times from irregular locations. They were distinguished by their unusual encryption, which did not appear to be OTP or any other conventional Razvedka cipher.

Hermann and the coding bay had never spent much time on the Orpheus transmissions because they were infrequent and had always been graded low-priority—until now.

Victor believed Orpheus was a mole within the British secret services, and that the transmissions were coded messages between himself and his Soviet handler. Coming from anyone else, Hermann would not necessarily have dismissed the possibility out of hand, but it was not so plausible coming from the man who cried mole.

Someone stood up for her stop, and, as if she hadn’t noticed Hermann before, gestured to her empty seat. Hermann shook his head, excessively deferent, and said, “My stop’s next.” His hip ached in protest. She passed by him, and he, gripping his cane, let someone else sit down instead.

“Orpheus is top priority, Gottlieb,” Preston had said. “The ‘why’ is unimportant to you. Only the how. I’ll need your files.”

“My files?”

“The Orpheus records,” Preston snapped. “I’m taking them upstairs.”

“Victor can come get them himself if he wants them,” Hermann was tempted to say, but did not. Victor had avoided Hermann for the last ten years—today would be no different.

“When will I get them back?” Hermann asked instead.

The intercom announced his stop, Wheaten Street, coming up next. Hermann heard it without much relief. Normally, he left his work at work. At home, he was a regular person, with regular hobbies, regular hopes, regular secrets. But as the train slowed and stopped, work clung to his thoughts: the unreadable transmissions, the unknown mole, even the absent Victor’s ever-present cold shoulder.

And normally, he did not spend the evening alone. But tonight, he would. His habitual dinner guest had left town.

Hermann emerged into the sun and turned up Wheaten Street. He looked up at Newton’s building as he passed it, eyes climbing to his third-floor window. The light glared off it, shielding it from his eyes, and for a second in the evening sun he felt dislocated from time, terribly out of place. Something was wrong, he thought, something was horribly wrong. The light moved as he did, and he saw that the curtains were drawn, like always.

And anyways, nobody was home.

Hermann turned a corner, walked another block, and turned onto his street, Airedale Street.

On the stairs inside of his building, he heard music. For a moment he thought a neighbor was listening to Liszt at a disrespectful volume, for those were the unmistakable bars of El Contrabandista. But as he reached the top step, the notes stumbled.

Something like a smile disturbed the blunt lines of his face. Hermann took out his keys quietly.

The heavy opening motif plunged down again before stopping abruptly. The piano player restarted a few measures back.

Hermann unlocked and opened the door softly, and the playing continued at full volume. It was dark in the front hall—the first blue shadows of night were falling in from the kitchen doorway at one end, and the front balcony door at the other. Warm light came from the living room doorway, because someone had turned on a lamp.

Hermann slipped off his shoes and stepped into his slippers. He closed the front door with care, but as soon as the bolt clicked home, the song abruptly changed.

“Liszt giving you difficulty?” said Hermann, emerging into the light and leaning against the living room door frame.

“Liszt?” Newton, sitting at Herman’s upright piano, made a scoffing sound. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Strange,” said Hermann, beginning to unbutton his shirt cuffs. “I thought for certain I heard someone practicing El Contrabandista as I came in.”

“Now why on Earth would I do a thing like that?” said Newt. He made as if squinting at the sheet music, while continuing to sound out ‘In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida’ with his fingers. “First of all, the Contrabandista is outrageously difficult. Even Liszt couldn’t play it. Second, it’s nowhere near as badass as Iron Butterfly. And third, I don’t ‘practice.’ I’m just good.”

“Is that so?” said Hermann, switching to his other cuff.

“Yes. And if I did have to practice,” Newt said, finally looking up at Hermann, “I certainly wouldn’t allow anyone to witness it. I have to maintain my pristine reputation for effortless genius.”

The prodigal engineer was a short but leggy man, dressed for work in one of his unprofessional patterned shirts, sans tie. He had thick-framed and thick-lensed glasses. His large forehead was accentuated by a high sweep of hair, one he maintained carefully even as it passed out of style. He peered at Hermann with heavy-lidded green eyes.

“I would not call your reputation in this flat ‘pristine,’” Hermann said.

“But you would call it genius?”

“I would say,” said Hermann, approaching the piano, “that anybody who can play El Contrabandista will be eligible for consideration for such a title.”

“Hmm. Doesn’t sound worth the hassle,” said Newt. “What’s your policy on Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2?”

He played the opening bars.

“I like El Contrabandista,” said Hermann, leaning on the piano. “It sounds like an argument.”

“Can’t possibly imagine why that would be appealing to you,” Newt said. But he was unable to keep from smiling as Hermann leaned in and kissed him on the cheek.

“I thought you’d already left for the conference,” Hermann said, crossing the living room and going into his bedroom.

“Decided to go tomorrow morning,” Newt called to him as Hermann opened his closet. “But I went to the station this afternoon and sent my things ahead.”

“Sent them ahead so you could...?”

“Yes, so I could ride up on the Bonneville. You think I’m going out to the countryside in June and not going riding? Come off it.”

Newt played a few more measures of Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.

“Man, it’s been years since I was up at the Estate,” Newt said. “I didn’t even have the Bonneville back then.”

Hermann hated Newton’s motorcycle. He chose on this occasion not to comment.

“How was work?” Newt called. “Everyone miss me already?”

“Wesley does,” Hermann answered. Wesley was their older labmate, a strange, friendless engineer with a couple of consuming obsessions. “Weeks sent him to my desk, to divide the labor on Orpheus, and all he wanted to talk about was—”

“Fermat?”

“Fermat.” Hermann sighed, frustrated.

“Never gets old, does it?”

“I wish someone would solve that blasted theorem so I would never have to hear about it again,” Hermann said, reemerging from his room in a sweater. “If he would just choose something useful to devote himself to, like Poincaré, or even something just interesting like the Riemann—”

“Hey, don’t you get him started on Riemann,” Newt said, breaking off his playing to point at Hermann as he passed. “I’m going to get that bastard myself.”

“If you really still think a machine is going to solve the Riemann hypothesis, you’re a romantic,” Hermann said, going into the kitchen.

“Guilty,” said Newt.

“In any case,” Hermann said, as Newton resumed with something more melancholy, “Wesley finally stopped talking long enough to ask where you were. I told him you’d be gone until Tuesday.”

“Did he say he’d miss me?”

“He said, ‘It’s always so quiet when Newt is gone,’” Hermann replied, imitating Wesley’s deeper voice. “And I agreed.”

Newt made a face. He resumed Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.

“So Weeks has you back on Orpheus? What, is it slow upstairs?”

“Actually—Victor,” called Hermann, violating his minimal-work-talk-at-home rule due to stress. “Preston the watchdog came down and told us it was top priority, all of a sudden. Victor wants full traffic analysis, cross-referenced with travel records of active personnel.”

“Which personnel?”

“Ops and officers. He gave us an enormous list.”

A stumble on the keys, and a correction.

“Preston took all my Orpheus files upstairs. I’m sure Victor’s in his office poring over them right now.”

“He didn’t come down himself?”

“He never does.”

Newt paused, and then started playing the opening of the Contrabandista again.

“Why Orpheus now?”

“Preston wouldn’t say,” Hermann replied. He took out a pot and began filling it with water. “He thinks it’s a mole.”

“Ah. Typical.”

Hermann made a noise of assent and shut the water off.

Newt’s hands slowed down, playing lightly.

“He could be right, though,” he offered. “I mean, this is exactly how the Americans finally caught Bowen.”

“Found him out,” Hermann corrected.

Newt rolled his eyes. “Well they nearly caught him.”

With a click-click-click the stovetop turned on.

“And imagine if they—or we—had,” said Hermann, not archly enough to disguise a genuine bitterness. “Maybe Victor would be tolerable.”

“Maybe he would tolerate you,” Newt said.

“Doubtful,” said Hermann, putting a lid on the pot.

The musical notes tumbled over each other. Then abruptly, they stopped.

“But how did they lose him?”

“Bowen?”

“Yeah.”

“What do you mean?”

The piano lid shut. Newt appeared in the kitchen doorway, massaging his left wrist. Hermann was sitting at the table peeling potatoes.

“Do you really think they knew? At the Estate?”

“Newton, what do you—”

But Newt was distracted by the appearance of Laplace. “There he is!”

Hermann turned and watched his cat lumber into the kitchen.

“Leave him alone,” Hermann said pointlessly. Newton was already pursuing the cat into the pantry. Laplace was extremely fat and unpersonable, and staunchly resistant to Newton’s advances. From the pantry came a predictable hiss and predictable cry.

“Hermann,” said Newton plaintively, reemerging into the kitchen.

“He hates everyone.”

“But I’m not everyone. I saved him. I gave him to you.”

Newton had found the bedraggled cat on his balcony a few years before. He was unable to keep it, because he kept birds, and the cat had a hunger in its eyes.

“Who is this ‘everyone,’ anyway?” said Newt. “When has Laplace ever met another human being? Who have you been bringing round to harass the cat? I just don’t understand why the Estate people let Bowen stay after the warrant was issued,” he said, swerving between topics without pausing for breath.

The Division’s infamous former Vice Chief, deep cover Soviet spy Robert Bowen, cast a long shadow—a shadow ten years long. Hermann had known him a little, through Victor. Bowen had been just as charming as his reputation, just as finely and eccentrically dressed, with his one drooping eyelid and his attentive smile. No one with their head on straight would have accused him of being anything as outrageous as a Razvedka agent.

But he was. And when, after more than twenty years undercover, the Americans discovered his treachery, Bowen fled. He hid out at the Estate, the Division’s training ground in East Anglia.

Division Headquarters issued a warrant for his arrest, and a red-alert to all employees. But, inexplicably, he did not flee the country right away. He stayed at the Estate for two days. Even more inexplicably, the Division employees who worked there—teachers, trainers, and support staff—let him stay there. They hosted him, did not tell London he was there, and then, when he announced that he was leaving, they did nothing to detain him. Somebody drove him to the train station, and he traveled the last hundred miles to Great Yarmouth Port, where a Scandinavian merchant in the U.S.S.R.’s employ picked him up, and smuggled the mole away via the Baltic to freedom.

“I’m sure I don’t know,” Hermann said, looking back down at the potatoes. “You used to work at the Estate. You knew those people.”

“Used to,” said Newt. “And almost everyone was fired.”

“Ask Caitlin.”

“She was fired too,” Newt said, as if Hermann didn’t know that.

“You’ll see her next week, won’t you?”

“At our gig? Yeah.”

Newt wandered to the stove and opened the pot.

“I see her every week, Hermann. That doesn’t mean she wants to talk about it.”

Newt shut the lid.

“I just don’t get it,” he said. “After all these years, I still don’t.”

“As I understand it, the Americans found transmissions corresponding to a mole in the British service. They matched the locations, times, and dates to his travel patterns, then brought the evidence to Whiteha—”

“No, I understand that,” Newt said, sitting down across from Hermann. “It’s the Estate thing I don’t get.”

Hermann handed him a paring knife.

“I don’t understand why he even went there at all,” said Newt, picking up a potato and beginning to peel. “So the Americans tell us on Friday. Someone tips him off. He skips town. Goes to the Estate. But he stops there. Then on Saturday, the scandal breaks. And he stays there.”

“Yes.”

“Until Sunday.”

“Yes.”

“That’s what I don’t get. Why did he stop? Why didn’t he leave? It’s not that far from the port. He could have left the country on Friday, before his photo was sent out to every border crossing in Western Europe. Why did he wait?”

“I’ve no idea,” said Hermann frankly.

“It’s not how I would have done it,” Newt commented, putting a potato in the bowl.

Hermann said nothing.

“Maybe he had misgivings about defecting,” Newt said. “I mean, it’s one thing to serve the Raz at a comfortable distance for twenty years. It’s another thing to actually live under Soviet rule.”

“Perhaps,” said Hermann.

Something in his voice made Newt glance up at him.

“What I really don’t understand is the Estate staff,” Newt said, looking back at his potato. “Why didn’t they rat him out?”

“He might have interfered with the alarm call somehow,” suggested Hermann. Newton frowned. Engineering and circuitry genius he may have been, but the human intricacies of operational spycraft never came easily to him.

Hermann put a peeled potato in the bowl of water and started on the last one.

“The thing is,” Newt said finally, “I don’t even think any of the Estate staff were actually turned. They weren’t his agents. I knew them back then,” he said. “And I saw the reports, afterwards. During restructuring. None of them were on the lists. They weren’t traitors.”

“It would only take one,” Hermann pointed out. “One traitor to take the alarm call, to cover for him.”

Newt just frowned and shook his head.

“I don’t know,” Newt said. “I think... I think he just talked them into it.”

This vexed Newt for some reason. It vexed Hermann too. It vexed Victor, who had been a great friend of Bowen’s. Victor, Robert Bowen, and Charles Rennie—they were the famous trio, Victor and the ‘Twins.’ Nobody had been taken in by Bowen’s charm more than Victor had, and no one had been more blindsided. Except perhaps for Rennie; but he was dead.

Hermann put the last potato into the bowl of water. “It’s certainly strange,” he said, standing up.

“I’ll never understand it,” Newt said, as Hermann went to the stove.

“Well, I don’t think it’s likely to come up this weekend.”

“Bowen always comes up,” said Newt, putting his feet on Hermann’s vacated chair. “If we don’t bring it up, the Americans do. Honestly, they were so pissed about Bowen, you’d think it was them he double-crossed. Like, it’s been a decade. Get over it.”

“I think that’s the hope,” said Hermann. “At least from the way Weeks talked about it.”

“Oy. Weeks. What a nebbish.” Newt was slicing the potato peelings into smaller and smaller pieces. “He’d lie down in a puddle and let the Americans walk right over him if they told him they didn’t want to get mud on their shoes.”

“Frankly I think he would let any authority figure do so,” Hermann said, giving the potatoes one last stir and shutting the lid.

Newt laughed.

“Strong words, coming from you.”

Hermann dried his hands primly on a dishtowel. “Exactly.”

“Maybe the mole will strike again this weekend,” said Newt. “Send some frantic messages from the conference. Maybe Orpheus is Bowen, Mark Two. Bowen, son of Bowen.”

“I certainly hope not,” said Hermann.

“Can you imagine Victor’s face?”

“I doubt that he would survive another Bowen,” said Hermann honestly.

But that was impossible anyhow—Victor had no one left to betray him. He had made sure of that.

They ate dinner and retired to the living room, where Hermann tried to catch up on his reading and Newton made unappreciative comments about the Debussy record Hermann had put on specifically to irritate him. Newton was rereading The Fellowship of the Ring, as he did annually, with his feet tucked under Hermann’s thigh.

“This is my record player, Newton, if you take issue with my record selection, you can go home. To your record player.”

“I’ll beat you at chess next weekend,” said Newt, turning a page. “Enjoy your two-week reign while you can.”

“Your belief that beating me at chess gives you legal claim over the music selection—”

“Not legal claim, but it does give me veto power—”

“—is almost as pathetic as your belief you are better at chess than I am—”

“All flukes,” Newt said, turning another page rebelliously.

“Right. Whatever helps you sleep at night. Speaking of which...”

Hermann glanced meaningfully at the wall clock.

“Yeah. I’ll go soon,” Newt said, making no movement to do so. His eyes wandered across the curtained windows behind Hermann’s head.

“Are you thinking about the conference?”

Newt shrugged. “Are you thinking about Orpheus?”

“It’s nonsense,” Hermann murmured, trying to see if he believed himself.

Newt stared at the curtains.

“The conference will be fine,” Hermann said.

“Yeah,” said Newt. “I’m just curious about this new CIA gadget. That’s all.”

Hermann frowned a little at Newt. Usually, the man’s curiosity translated into excitement, but instead, he seemed preoccupied.

“Weeks hasn’t told you anything?”

“Not really,” said Newt. “He might not know anything. It’s a high-level thing. It might even be a Victor thing. I heard there’s going to be a whole treaty... the works.”

Something, some chord in his voice, suddenly woke in Hermann the idea that Newton was lying. He was hiding something. The idea came from nowhere, like a brick flung through a window—but now the window was smashed, and there was the brick. This was their life, after all; for all its comfortable routine, ordinary tiffs, and other shared intimacies, the world they lived in together was a world of secrets. There were some secrets Hermann could not share.

Hermann had a long-held superstition that there was something inside him which needed protection. Something that needed protection from external intercession, or perhaps something from which the world needed protection. This superstition was what had drawn him into the world of secret intelligence in the first place—not the intelligence, but the secrets, the guarding of all those secrets.

If his heart was an ocean, like anyone’s, Newton had charted it. There was one last anchor Hermann guarded. He guarded it not for what it held, but for the security of its untouched existence.

Did Newt know that he was holding back? Hermann averted his eyes from Newton’s own pockets of secrecy—his dark labyrinthine flat, the experiments he did there. Hermann did not ask. Not out of consideration, but self-preservation.

So all he said was: “Are they even going to let you look at this ‘gadget’?”

“Do not disguise your envy as disparagement,” said Newt. “It’s very unattractive.”

Hermann rolled his eyes.

“Officially, according to my schedule, no. I’m just running workshops. The usual how-to shtick. For locals and my fellow Americans.”

When Hermann closed the journal a half an hour later, Newton was dozing with his head on Hermann’s lap. When he said softly, “Go home, don’t fall asleep here,” Newton murmured, “Uh-huh.” Some time later, when Hermann was settled in bed on his good side, one pillow between his knees and one behind his back, the bed creaked and Newt crawled in beside him. In the morning, he was gone.

For what was now widely considered a highly productive professional partnership, Newt and Hermann’s acquaintance had begun in a rather quaint manner.

Hermann was born to a Jewish family in 1930 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Bavaria. They fled Germany when he and his sister were small, and settled outside London. His father Lars Gottlieb was a doctor, and an unforgiving sort of man. Conforming readily to the spirit of their new nation, he sent his children away to school and rarely saw them. Hermann eventually found his way to mathematics, and then to Cambridge.

It was an old recruiter, a don named Thurston, who spotted Hermann at Cambridge. Thurston was an ageless professor of Old English literature and Germanic philology; Gottlieb, reserved, intelligent, and multinational, caught his eye. He introduced Hermann to Victor, a war hero ten years Hermann’s senior and a rising star in the Division. Victor took a liking to him. He made the right introductions, handled the vetting and interviewing, and saw to it that, upon completion of his mathematics degree, Hermann Gottlieb entered training at GCHQ in Cheltenham. So began his illustrious cryptographic career, under Victor’s convivial eye.

Newt’s recruitment a few years earlier had been, characteristically, less passive. He was born to a large German-Jewish family in New York City, on the Lower East Side, in 1932. An emotional and intellectual terror from a young age, like many child prodigies, his case was taken up by an affectionate science teacher. His parents were happy to hand him off, at the age of 12, into the care of MIT.

Seven years later, he was selected for a yearlong research fellowship at Oxford University. A prodigy of American birth and German breeding, pursuing his doctorate in electrical engineering at the age of 19, he attracted attention on paper. His antics attracted even more attention on campus. He burst in uninvited at parties to give speeches on archaeological history or the Riemann hypothesis, or withdrew abruptly from formal gatherings to tinker in his room, where, if rumors were to be believed, he was inventing a new kind of telescope, a cordless telephone system, a personal-use missile detection radar.

Such rumors, though surely false, attracted the network’s attention. Oxford’s venerable intelligence tradition was rich with both targets and recruits; unfortunately, as a result, barely trained new recruits were the ones to surveille the targets. Newt noticed his watchers. He figured out who they were. Then he marched up to one and demanded, with a hierarchical misunderstanding he would never outgrow, to be taken to their leader. He wanted a job.

Within two years, Newt was the star child of the Division’s Hardware department. Absurdly young, he was a hot poker in the seat of hardware’s pension-age engineers, slow old men with secret medals from the wars. Newt’s mission was to drag the department out of the past and into the future, with no pause at the present, and though the veteran engineers fought him every inch, they were invigorated by this electrifying nuisance. With Newt in the hot seat, hardware churned out advances in surveillance technology, newer, faster, smaller.

Every couple of months, Newt went up to the Estate to train officers and ops on the new gear. It was at one of these workshops, a mild February weekend in 1962, that he was doing a puzzle under the table during a lull. It was the weekly number puzzle in the Sunday Times, which he had pinched from the boarding house breakfast room that morning. He complained to his neighbor, a brightly dressed officer with a crooked jaw, that the Times number puzzle had dropped sharply in quality since the new year.

“I used to spend all afternoon on these,” Newt said. “Now they take me 5 minutes.”

“That bad, is it?” said the officer.

“Awful,” Newt said with American frankness. “Either the puzzle department is under new management, or the old manager had a stroke.”

“Actually, he quit,” said the officer, who ran the German desk in London Headquarters and whose name was Victor. “I know him.”

“You do?” Newt said. “Why’d he quit?”

Victor leaned in confidingly. “His work’s gotten too busy.”

Catching his meaning with surprise, Newt exclaimed, “He works here?”

“As a matter of fact, I hired him myself,” Victor said with an easy smile.

Newt, not one for internal regulation, asked for the puzzlemaster’s workname and posting. He wanted to write him a letter thanking him for a consistent challenge. Victor, genial son of the old boys’ network, heir to mantles passed down simply by virtue of knowing the right people, was happy to share the information.

Hermann received the letter a week later, addressed to his workname and signed with a stranger’s initials. Thus began a confidential correspondence under cover of pseudonyms.

✦

Saturday

June 2nd, 1973

The Estate

The Estate was west of Norwich, a half an hour’s drive from the Broads. It was by all appearances a country manor, with a sizeable collection of outbuildings and acres of fields and forests. An officer named Marsden had left it in trust to the Division sometime between wars. His much younger wife, imperious Frenchwoman Mme Marsden, became the caretaker. For the next 30-odd years, it had served as the Division’s training center, where new operatives learned and old officers refreshed their skills. Since the Bowen affair in 1963, its security clearance had been severely downgraded. These days, it was primarily a temporary residence—a safe house, a place to debrief, and occasionally, a venue for diplomatic functions.

The conference with the Americans was Friday through Sunday. If all went well, it would be followed by a high-level treaty meeting the next weekend. It was top-tier only. The terms and stakes of the meeting were top secret, and so, widely known around the grounds.

Newt spent the first two days of the conference collecting intelligence. By Saturday, he knew several things. He knew the CIA gadget was extremely valuable. He knew the Brits were trading something of equal importance for it. And he knew where both gadgets were being kept: inside the conspicuously guarded stables.

Luckily for Newt, he was quartered in the boarding house, which was spitting distance from the stables. From this position, he had occasion to learn something else: Case Officer Raleigh Becket was in attendance.

He was not on the roster for any of Newt’s CO workshops. So what was he doing here? And why was he going in and out of the stables?

Becket was the head of the Austria station, if Newt’s memory was correct, which it always was. He was young, handsome, ex-Marines. Hermann had worked with him on his first and last away mission. Becket never seemed like a spy to Newt, except in the most vulgar, Fleming sense. He was too conspicuous, too shiny.

Becket also had the distinction of being the only named officer in the top secret file Newt had received in February. Over the last few months, Newt had given that file quite a bit of thought.

On Saturday, Newt finished his workshops and considered his options for the afternoon recess. Entering the dining room, he was accosted by the hovering Mme Marsden. She was a small, energetic elderly woman; age had not dimmed the vividness of her wardrobe. She still wore the same pearls Newt remembered.

“Newton, dear, how are you?” she asked. “I have been so busy, I have hardly talked to you—we have not been so busy here in years! Your room is comfortable? Newton, you bad young man, you never visit me anymore. It gets so lonely out here, you know, without the trainings. You should ride up your motorcycle more. Bring that girlfriend, how is she?”

“Cait’s not my girlfriend,” Newt patiently reminded her. “Mme Marsden, don’t you know that I’m married?”

She gasped. “Married?”

“Yes! Married to my work!”

“Bah!” She slapped his arm with her ring-studded hand. “One of these days you must settle, Newton. You are getting old. You will not have this hair forever. You must use it to attract a wife before you lose it.”

Newt laughed.

Mme Marsden squeezed his arm. “This is why I miss your visits, Newton. You smile and laugh, not like these Englishmen—they never do. We French only laugh, we do not smile. Still, one misses it.”

Newt smiled fondly. “Mme Marsden, you’re such a flirt. Caitlin is doing well, though, thank you for asking. We play music together. We have a show in London on Wednesday. You should come see us play.”

“London! London is not good for my lungs,” Mme Marsden said. “Or my headaches. Or my heart. Does Caitlin still work in the Black Chamber?”

Newt raised his eyebrows. Is she losing her memory?

“No, Mme M. She worked there before she worked here. But she was fired. She was here during the...”

“Ah, of course, of course.” Her face closed off abruptly, like blinds had fallen. “Terrible business,” she murmured, eyes roaming away from him.

“Yeah,” was all Newt came up with. She was a proud woman, after all, and the Bowen affair had taken place on her watch. Even to say his name to her felt like a vile insult.

“He was always good to me, you know,” she finally said, lifting her eyes to Newt’s. “Those boys, they always were. The twins and the tagalong. There were so many summers they spent here, training their recruits. I miss them all, the trainees. I miss seeing them grow. Most of all, do you know who I miss, Newton? That Charles. His ‘twin.’ And you know, I miss Victor too. It is like they are all gone.”

“Victor’s still here,” Newt said.

“He is not,” Mme Marsden said. “Victor is gone.”

Newt looked away.

“Newton, mon cher, your room. It is comfortable? I am sorry to put you up in the attic with all the spiders, but the beds are more soft there.”

“It’s great,” Newt said, putting his hand on her arm. “Very cozy. I don’t think my neighbor much cares for me though.”

“Your neighbor? Mr. Rosewater? He was rude to you?”

Mme Marsden turned, squinting across the crowded dining room. She spotted him.

“Ah. There he is. By the French doors.”

“Is he American?” asked Newt.

“He’s the American, mon cher. He is the liaison,” she said. “This is why I give him the nice rooms. But was he rude to you, Newton?”

“Oh—it was nothing,” Newt said, craning his neck to look at the liaison. He was thin and smooth, with the youthful vitality of American military bureaucrats. When he replied to someone’s greeting, Newt could see his gold fillings flash across the room. “...Pounding on my door this morning asking if I had used up all the hot water. Calling me a nancy-boy. That’s all.”

“Hot water!” she said, scoffing. “He probably used it all up himself. These Americans. So decadent.”

“No wonder they hate the reds so much,” Newt said. “Do you know what his title is?”

“He is the R&D Director for the CIA,” Mme Marsden replied promptly.

“The whole CIA?” Newt was impressed.

“Yes,” Mme Marsden said. She shook her head. “I should have given him a room in the basement with his colleagues.”

✦

What Victor had told Newt in 1962 was entirely true. Hermann had been forced to resign his enjoyable side job as puzzle editor because he was being fast-tracked for promotion in his top secret posting in a top secret lab at Menwith Hill, North Yorkshire. There, GCHQ shared a surveillance base with the Americans, and their cryptography partnership was being championed by none other than Washington liaison Robert Bowen.

When he received Newt’s first letter, Hermann was close to drowning in this institutional riptide. He was paddling out in the waves without a map or star or white whale to keep him company, and so he did something peculiar and unadvisable with the letter: he answered it.

Within a month they were writing twice a week. They were careful to avoid work topics, particularly Hermann. His little North Yorkshire flat was government-owned, so their letters could be read at any time. His correspondent never asked about the particulars of his work, nor detailed his own, and Hermann appreciated his tacit respect of this boundary. From this unspoken understanding he extrapolated swaths more. Hermann roamed the slopes and swamps of his lonely psyche, plucking material for his letters; he mistook his sparse clippings for meaningful confessions, and he mistook his own footprints for his correspondent’s.

Back in London, Newt was invigorated by his challenging and clever correspondent. Finally, he thought, he had found a peer in his field; not some arthritic engineer and not some hungry young ladder-climber. The puzzlemaster seemed equal to every topic Newt threw at him, except for modern music—he appreciated Newt’s speculations on paleontology, his inflammatory opinions on classical composers, his bizarre application of subjective idealism to the Space Race. The puzzlemaster returned with some fascinating ideas on the philosophical implications of transfinite math and the first compelling case for opera that Newt had ever heard. They also shared a passion for the Riemann hypothesis, and Newt divulged the truth of his personal project at Oxford: he had been trying to build a calculating machine to find Riemann Zeros.

Sitting on his small wrought iron balcony above the courtyard in North Yorkshire, Hermann spent whole evenings drafting his replies. Newt devoured each on his crowded commute, drafted his reply in his head all day at work, and typed it out in a single draft when he got home. For Newt, their correspondence was the natural extension of the Sunday puzzle. Hermann did not view it with the same pragmatism.

✦

Hermann was one of the specialists on the Division team being prepared for the new American cryptographic partnership. It was all part of Bowen’s project to bring the American and British networks into closer alliance. London smiled on Robert Bowen like a proud father, and as he drew up the charters in Washington, glasses were clinking in Moscow. But abruptly, in January of 1963, the Americans backed out of the partnership. A discreet emissary flew in from Washington and met with the deputy head of the Foreign Office in a soundproof room in Whitehall; when they emerged, the charter was scrapped and Bowen recalled to London.

His program terminated, Dr. Gottlieb was recalled from North Yorkshire. After ten months, Newt’s correspondent fell abruptly silent; his letters went unanswered for one week, then two, then returned, roughed up and stamped: “No Forwarding Address.”

✦

Saturday

June 2nd, 1973

The Estate

Newt returned to the attic for the late afternoon recess. Was his neighbor really the American liaison? That would be a stroke of luck. He walked by Mr. Rosewater’s door on his way to his room, and paused.

It was ajar, which meant he was inside. Or was he? Newt stood still, but heard nothing within. He couldn’t see anything interesting through the crack. If he just poked his head in…

Footsteps sounded on the stairs and Newt hastily resumed forward motion. He went into his room and shut the door.

He collapsed on his twin bed under the eaves and read Fellowship for a while. Then he slid off the edge of the mattress into the narrow space between the bed and the wall. Lying on the scratchy carpet, he investigated the crossbeam under the headboard. A handful of initials were carved into the wood, some of them forty years old. He gazed at C.R., wondering if it was Charles Rennie, Hermann’s old CO.

Newt settled on his side and watched a spider at work between the beams. Lying there in the stuffy attic air, he spun thoughts of Becket and the blueprints, the treaty, the stable, Mr. Rosewater’s gold teeth. He drifted into a doze.

Newt woke to the sound of footsteps in the creaky hallway. “Check the other rooms, will you?” said an American voice, and he heard someone open the door next to his. Mr. Rosewater was home.

It was still light, but Newt, dazed, could not see the clock from behind the bed. His mouth was very dry. He was about to stand when his door opened. Under the bed, he saw shiny patent leather shoes, and then the door closed again. “Empty,” said Raleigh Becket’s voice.

Newt heard Becket’s feet walk next door, then Mr. Rosewater’s door closing and locking.

Awake now, he climbed as quietly as possible onto his bed. The foot of his bed was against Rosewater’s wall. He knelt at the end and pressed his ear to the wall. Too muffled.

As carefully as he could, he climbed off the bed and crept across the room to the dresser. Fortunately, it was a small room; unfortunately, it was a creaky attic. Teeth gritted, he unbuckled his surveillance demo kit and rooted around until he found what he was looking for: his mechanic’s stethoscope.

Newt crept back to the bed and put the stethoscope into his ears. In a pinch, the analog tricks still worked best. He put the other end to the wall and listened.

“...the transmitter blueprints.”

“Of course. But I gotta say, I’m much less interested in the blueprints than in the Greenwich file.”

“Yes, sir?”

“He was your guy, wasn’t he, Becket?”

“Birch?”

“Who? No—Greenwich.”

“Oh. Oh, yes, sir. I was his contact.”

“Will I get a look at that file? Maybe even the unredacted version?”

“Yes, sir,” said another voice. “The courier is bringing it up along with the blueprints tonight.”

“Good. I want to see it before the recess. And I’ll make sure you gentlemen get a look at the transducer before tomorrow night.”

There was a pause, or something was happening that Newt couldn’t make out.

“Right. Great. I’ll see you fellas tomorrow evening.”

“Sir.”

Fellas? Who was the other speaker?

There was a sound of someone standing up, and then footsteps to Rosewater’s door. It unlocked and Becket walked by his bedroom door and down the stairs.

Newt took the stethoscope out of his ears. He slid off the bed and into the gap again. He wedged himself in between the bed and the wall, legs folded, chin on knees, thinking.

The conversation all but confirmed his suspicions: this CIA-Division tech exchange involved the transmitter he had glimpsed in February. Becket’s presence was the first definite clue, but the mention of Greenwich made it certain.

The transducer...

Newt needed to take some precautions first. He checked on the spider (web complete, spider MIA), then unfolded himself and climbed out over his bed. He grabbed his jacket and wallet and barreled out the door—and nearly ran right into someone.

“Excuse me,” snapped Preston. He was coming out of Mr. Rosewater’s room.

“Oh!—Preston?”

“Dr. Geiszler,” said Vice Chief Victor’s assistant. “Do you have some business up here?”

“Sleeping?” said Newt. “This is my room.”

Preston threw a glance at the room behind him, and Newt became aware of a quiet conversation going on inside. He followed Preston’s glance through the half-open door.

Victor was in there.

Newt paled slightly. Had he been in there, the whole time, without saying a word?

He looked back at Preston, who was giving him a warning look.

“This is Mr. Rosewater’s room, isn’t it?” said Newt.

“Chatting with the guests, are we?”

“Not as such,” said Newt, putting his hands in his pockets. “We had some words about the hot water this morning.”

There was the sound of a chair from inside the room, and Preston flashed Newt another warning look.

“I suggest you keep from bothering the American liaison, Geiszler. We don’t need to remind you how important this conference is.”

“Right,” said Newt. For a second, he’d felt curious to see the Vice Chief outside his office for once—but self-preservation won out. “I’ll be going then.” He started walking backwards.

“Where?”

Footsteps sounded from behind the door.

“Into town,” said Newt. “To call H—ome. Call home. And do some errands. Do you need anything? Stamps? Smokes?”

“Thank you, no,” said Preston coldly.

“Right then,” said Newt, and turned tail down the stairs just as he heard the door open.

He hastened off the Estate and into town. It was a short ride on the Bonneville, and the cool spring air calmed his nerves.

✦

In January 1963, Hermann returned to London. Victor seized the chance to have his protégé transferred into his section. Bowen, too, was back in London for the first time in a few years. Following the unknown unpleasantness with the Americans, the Division cleared Bowen and petulantly promoted him—thanks in no small part to Victor’s lobbying—to Vice Chief.

In London, Dr. Gottlieb’s focus shifted from the advancement of Division encoding methods to the unraveling of the Razvedka’s. Victor had an exciting new project to put him on.

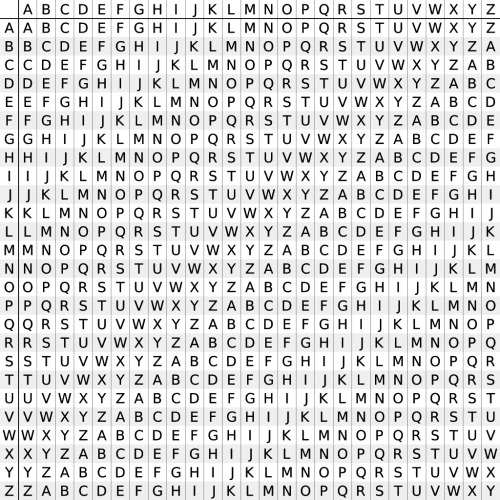

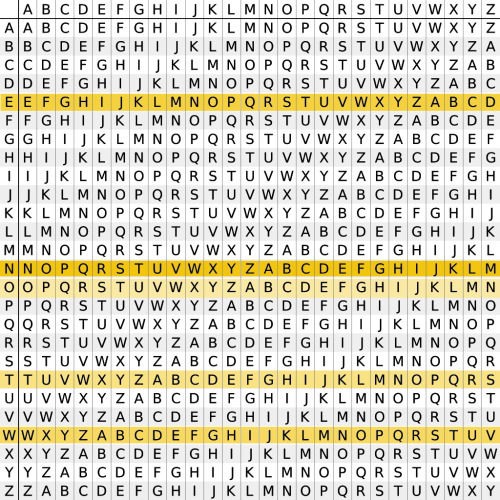

A year before, a Soviet cipher clerk had defected, codenamed Raspberry. In his lengthy debrief in a Canadian hotel room, Source Raspberry revealed that there had been a manufacturing error with the Russians’ onetime cipher pads. They had accidentally manufactured duplicates of a set. 10,000 formerly unique encryption keys were now circulating in duplicate. On their own, messages from a onetime pad were unbreakable. But two messages from the same encryption key could, if matched, be deciphered.

Source Raspberry said most of them were in use in Eastern Europe. Victor was chief of the German desk, so Bowen handed him the reins of the so-called “twotime pads.” The project: construct a system to detect reused encryption keys. What they needed was not just a quick-calculating computer, but a computer with memory. At the time, no such machine existed in Britain.

Victor christened the operation Project Blueberry and assigned it to the Hardware lab. He was still in need of a mathematician when Hermann transferred back to London. Victor was quick to add his protégé to his pet project. At their semi-weekly status meeting, Victor introduced Dr. Gottlieb to Project Blueberry’s lead engineer, Dr. Newton Geiszler.

It had been two months since their correspondence was interrupted. Newt was confident that the puzzlemaster would write him back eventually. Given their work, Newt reasoned, he had probably been deployed to somewhere unreachable. For Newt, the mystery was on the back burner. And Hermann had no idea where in their vast organization to look for his anonymous correspondent.

That day, they shook hands as strangers.

They took an instant dislike to each other.

A week of intense friction followed. Then, in their third status meeting, Hermann spat out what Newt recognized, with a terrible sinking heart, as a turn of phrase from one of his letters. Hermann snapped at him, in front of everyone, to “cease his American palavering,” and Newt saw in his mind’s eye the longhand script criticizing a colleague at Menwith Hill base using the exact same terms. This man too was a cryptographer recently returned from a top secret posting in North Yorkshire. This was him, Newt realized. This was his correspondent—and he hated Newt.

✦

Hermann reacted poorly to the news.

It is a hard climb up out of the gulf between reality and fiction; Hermann refused to make it. He stayed at the bottom, subsuming his disproportionately crushing disappointment. Newt received, but could not parse, the distress signals he was broadcasting. Why was he so upset? Hermann himself did not know why. The real Newton had barged in and obliterated his own vague, idealized shadow. Before Hermann’s eyes that imaginary person vanished into the realm of forgotten fiction.

Newt had no idea how to deal with Hermann’s silent but intense reaction. With equal but noisier intensity, he focused everything on their work.

In circuit diagrams and failed prototypes, reams of data, algorithm after algorithm, they circled each other. Failure was followed by minor success, which was followed by major setback and days of arguing. Over two months, Newt designed a skull for the brain Hermann was writing. In March, Newt and his team began to build it. By the end of March, the Blueberry was complete. Its memory storage unit took up an entire room. Hermann installed his painstakingly constructed code, and it went online.

The Blueberry was designed to detect an OTP match, not to decipher it. Copious amounts of data—thousands upon thousands of undeciphered enemy messages—had to be fed in before a duplicate could be discovered. When one was found, the computer’s output would be the transmission IDs of the two messages which matched. These two enciphered messages were to be located in the records, and then taken upstairs to the busy coding bay, where a clerk would decipher both by hand.

For weeks, under the anxious eyes of its creators, the Blueberry swallowed and digested every OTP-encoded message since WWII. After a week, it had processed and stored every message up to 1950. By the end of week two it had reached 1959, and Hermann’s anxiety had nearly reached the breaking point. But it was here that they got their first match. An OTP from 1942, reused in 1959. The operation was a success. Their machine worked.

Up until then, Newt had harbored hope of reconciliation. This hope was fused to the success of the project: if he could build the Blueberry for Hermann, that would make it up to him.

What “it” was, Newt didn’t quite know.

Nor did Hermann. But he didn’t stay to find out.

Newt returned to the lab from their final debrief meeting to find Hermann emptying his temporary desk. The sight hit him in the gut. With no idea what to say, he aimed at something unimportant—something from the meeting—and began throwing darts at it wildly. Hermann in turn called him unprofessional, like always, and Newt told him he was impossible to work with, like always, even though it wasn’t true. It wasn’t true at all—the opposite was true. Working with him had been better than anyone, better than he had imagined from his mythical correspondent, and he could not say so, he could not say it. And Hermann, by all evidence, did not feel the same.

Three weeks later, Hermann was in East Berlin. Vice Chief Bowen was sending Charles Rennie on a surveillance mission, and Rennie needed a technician with coding expertise who spoke German. Hermann had volunteered. An unidentified object had crashed in the countryside, east of Berlin.

✦

Saturday

June 2nd, 1973

London

In Hermann’s flat on Saturday night, the phone rang. He let it ring once. There was no second ring. He waited, and after a 30-second pause it rang again. He picked up and listened: three clicks, a two-second pause, then four taps. The line went dead.

“Typical,” he muttered irritably, almost before hanging up.

Outside the air was cool and foggy, with a humid tang of rain. He was still buttoning his coat as he hurried out his front door and limped around the corner. The phone in the booth was already ringing.

“Four minutes is not enough time for me to walk to this one, you nitwit,” he said angrily into the mouthpiece, shutting the glass door behind him. “I barely made it.”

“Oy, you’re old,” replied Newton’s tinny voice. “Who even says ‘nitwit’ anymore? Old on two counts.”

“Need I remind you—”

“Focus, Hermann, I don’t have very much change. I need a favor.”

Hermann sighed in a put-upon manner that said, Go ahead.

“I need you to hide something for me.”

“Oh, excellent. Of course, Newton, please help me jeopardize my career. And yours as well. My pleasure. Do go on.”

“Yeesh, relax,” said Newton. “It’s a personal thing, not a work thing.”

“As if there is any real division between the two,” Hermann snapped.

If only you knew, Newt thought. “Bad day huh?” he said instead. “Did one of our colleagues do something untoward? Like ask about your weekend plans?”

“Please get on with it.”

“It’s in my apartment,” Newton said, sounding like he was looking around. “In the spot. Green box.”

“What spot?” Hermann said impatiently.

“You know where I mean!”

“I do not make a habit of visiting your nightmare of a flat, as you well know.”

“Hermann, I’m not saying over the phone, okay? Fortress of solitude. You’ll figure out where it is. Green box. Don’t touch anything else. Especially not in the workshop. And don’t forget about the lights.”

“I won’t,” Hermann said, remembering the time he did forget about them.

“And once you’ve got it, can you—”

“Yes, yes, I’ll take care of it.”

“And one more thing?”

“Yes?” said Hermann shortly.

“...Would you check on my birds?” said Newt.

“Jake has them?”

“Yes. Just make sure he has enough food and everything.”

“Yes—fine,” said Hermann. “Are you going to tell me what all this is about?”

“Not over the phone,” Newton said again.

“Then will you—”

“Not via post either. Just wait til I get back. I’ll explain.”

“On Monday night?” said Hermann, aiming for a put-upon delivery but delivering something more like gloom.

“Aw,” said Newt, with an air of realization. “You’re cranky ‘cause you miss me.”

“Is that all, Newton?”

“Yes, th—”

Hermann hung up.

Hermann stood in the booth a moment longer, nervously running his thumbnail up and down the ribbed metal phone cord.

The street outside was empty. Hermann took a detour to return to their block via Wheaten Street. Personal, he had said, a personal thing. Hermann did not believe him.

It had been ten years since he was trained as an operative, and almost as long since he had put those skills to use. The tricks, the vigilance came back to him now like it had been no time at all.

He saw no watchers outside Newton’s building, but walked past it without stopping and went home.

Then, instead of going upstairs to his flat, he descended into the basement. He exited the building’s back door and hurried around the periphery of the courtyard. He made a quick check in the alley, found it empty, and crossed. He hurried around the other courtyard to the back door of Newton’s building, and with his copied key and a last look around, he let himself in.

Hermann climbed to the third floor. He did not like going to Newton’s flat, his “Fortress of solitude.” The disorder of his laboratory-office in the Century basement was one thing (and what a thing it was). But the chaos of his flat had an... undefinable menace. Newton calls me paranoid, thought Hermann (trying one lock, failing, cursing the man under his breath, trying the second, wishing for a world where his partner did not have three separate locks with three separate keys on his one front door), yet it was Newton who had turned his flat into a bugged and bear-trapped labyrinth.

Hermann turned the doorknob and slid his thumb over the bolt so it would not pop back out (if it did, an alarm would sound), stepped inside, and carefully closed the door. He picked up the little wooden slivers that had fallen from the lock bolts and pocketed them—another security signal, to replace before he left. If the slivers were missing, the owner would know the locks had been opened and re-closed in his absence.

Newton’s combination of espionage tradecraft and near-farcical mad scientist tactics unnerved Hermann. It unnerved him, too, he thought, removing his shoes and stepping, socked, over the tripwire just past the welcome mat, that he had so much security for no discernible reason. If, God forbid, some inquiry did ever give the Division reason to search his home, their suspicions would immediately rise to red alert, simply from the outrageous apparatus of the place—all of it to hide, as far as Hermann knew, absolutely nothing.

Hermann flipped the switch outside the living-room-turned-bedroom to stop the sensor-activated floodlights from blaring. In typical Geiszlerian style, the rooms had been shuffled and repurposed. Newt’s unmade bed and half-open dresser lived in the front room. The wide street-facing windows were half-blocked by an overflowing personal bookshelf full of records and pulp science fiction. Music leaked from a radio in another room. Hermann turned on his flashlight.

It was very annoying of Newton not to tell him where to find this mysterious green box, though in a way Hermann desired the challenge. The box was probably in a sentimental or somehow personally significant place, because unlike Hermann, Newton had never properly trained as an operative. So, stepping over dirty discarded clothes, he looked inside of Newton’s upright piano, the bench, his empty guitar case. He felt behind all the books. He removed What’s Going On from the turntable and checked for secret compartments in the record player. He opened the back of the television set and found a short-range signal delay jammer—of Newton’s own design, but stolen from work. The delay was set to two hours, he noted. Newton had probably installed it so as to watch television shows after their broadcast hour.

Next Hermann shone his light on the door of the original bedroom, now Newton’s workshop. Locked. The music was coming from inside—Newton’s preferred pirate radio station, he guessed from the sound of ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ by The Who.

The workshop was the core of the bizarre little apartment. Hermann had never been inside it. When he looked at its lock, an apprehension of untraced origin tugged him away. Had Newton given him the key? Was it on his overcrowded keyring?

Hermann chose not to find out.

Instead he entered the kitchen, wondering how different the growth rate of communications technology in the British intelligence service would have been if it received the full brunt of Newton’s interest. Fortunately for communists everywhere, his laser strength interest remained laser-pointed at his personal tinkering.

The kitchen was primarily a greenhouse and a storage space. Hermann’s flashlight passed over a large telescope and a dissected motorcycle engine. Over the counter and sink hung a truly impressive wall of foliage. His light revealed a hose hooked up to the faucet. Probably hooked up to a timer. One mystery—Who waters Newton’s plants while he’s gone?—closed. Another mystery—How, if at all, does he drink water?—opened.

And does he eat? Then I’ll get on my knees and pray... sang Roger Daltrey from the other side of the wall... We don’t get fooled again... Otherwise, all was silence. No furnace or pipes hummed. Nor did the refrigerator.

The refrigerator.

Hermann threw open its door. No light turned on. Unplugged and empty. He stifled a snort at this—Freeloader, he thought, not without fondness—and opened the drawers. Empty.

He felt around the floor of the refrigerator. There—a clasp.

From below a dummy panel in the base of Newton’s unused refrigerator, he drew a small slim box. It was green. Triumphant, he replaced the panel, shut the fridge door, and examined the box by flashlight.

The green box weighed a couple ounces and rattled enticingly. It had a combination lock, four digits, which Hermann opened easily. He overturned it into his hand.

A small aluminum object fell out. Hermann could not immediately identify it. It was gunmetal gray, curved like an ear or a waning moon. He settled it in the center of his palm. It fit like it was meant to be there. He thought he could recognize Newton’s handiwork, but it was... neater than his usual designs. It was entirely closed up in its metal shell—the only visible part was a button on the inner curve and two collapsed antennas. If it was a radio, it was probably a transmitter, AM, with a minuscule range.

If it wasn’t a radio, well, then he had no idea what it was.

Hermann put it back in the box, snapped it shut, and left the apartment, resetting all the alarms and signals as he went.

June 3, 1973

Sunday

The Estate

Just at sunset on Sunday night, Newt left the boarding house by the back door.

He strode through the wet grass, which was growing quickly, still unmowed. The boarding house faces the stables, but he took the long way round behind the big house. It was a damp spring night, and the air was fertile and cool. Night was coming on quickly and stealthily. There was no moon.

He circled around the big house from the back and gazed up at the lighted windows. In the uncurtained window of the upper parlor, he could see Mme Marsden puttering. He walked on, keeping his distance from house. Flowerbeds of just-blooming peonies glowed with dew.

At the end of the garden plot, he stopped by a hibiscus bush. Through the last first-floor window, he saw a dark back and broad shoulders. Becket turned around, holding papers in one hand and a glass in the other. He was talking to two people—Victor and Rosewater, if the schedule Newt had purloined was correct. He checked his watch. It was 8:37 PM. He’d just set it by the radio clock in the boarding house dining room. If they kept to their schedule, they would be schmoozing until 9:15. He had plenty of time.

Newt circled around the front of the house. The wide front terrace, dotted with deck chairs, was deserted—the night was too cold. At last he reached the gravel driveway. He hurried back in the direction he had come, towards the boarding house and stables.

The stables lay low and long like a bluff in the hill. Newt paused on the edge of the driveway, turning to look back at the big house one more time. It was a blue-white mountain in the mist, rapidly turning gray in the vanishing sun. He saw points of light, but no people.

One light hung over the big front doors. In the fog, its white light made a solid cone over the entrance. It was best to walk in boldly, with no visible qualms. People usually overlooked a confident snoop. So he took off his glasses, put them in his pocket, straightened his coat and, with a last glance around, walked confidently towards the light. Crickets and frogs sang from the tall grass along the path. He ignored their warning song.

The inside of the stable was a cavern of poorly lit brown and gray blobs. The air was heavy with dust and hay, as if animals had actually lived in it some time during the last 50 years, which they had not. As Newt walked forward, some blobs resolved into a metal folding table. Behind it sat two vacant-eyed young corporals in U.S. Army fatigues, with a small radio murmuring on the table between them.

The fatigues seemed, to Newt, a bit extreme. They looked equally unimpressed with him.

“At ease, gentlemen,” Newt said, approaching jauntily.

“Who are you?” said the one on the right.

“Me? I’m the plumber,” he said.

They stared blankly.

“Oy, tough crowd,” Newt said, and clapped his hands together in a businesslike manner. “I need to take a look at the transducer, fellas. Make sure everything’s ready for tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?”

“Yes.”

“Can we see some authorization, sir?” said the one on the left, putting an intonation of doubt upon the ‘sir.’

“Authorization?” said Newt, playing it amused. “I built the damn thing myself.”

They stared blankly.

Should have just snuck in a back window, Newt thought.

“We haven’t seen you before, sir.”

“What? Me? Of course you haven’t,” said Newt, throwing his back into some blustering. “I just got here. By charter plane! And you ask me for authorization? Like you don’t know who I am? Why don’t you call up Mr. Rosewater and ask him? Ask him about my authorization, and see how he—”

“Sir,” said the one on the right, cutting him off, “We can’t let you in without ID. It’s that simple.”

“Oh,” said Newt, settling down. “ID? That’s what you want?”

They stared.

“Of course. My mistake. I’ve got that.”

Newton produced his wallet and pulled out a card.

He put his CIA building pass onto the table and slid it to them. “Here you go.”

It was his picture, and his number, and it was genuine. It was just that the “TEMPORARY” in large red letters had been covered with circular color-code stickers, the sort that security guards love and that army corporals are unlikely to know. And the name the name under his picture said “Neilson Garrett.”

“Thank you Mr. Garrett,” said the one on the right, sliding it back. “Was that so hard?”

“You’ll need to sign in,” said the one on the left, indicating a log.

“So sorry. Of course.” Newt took his pass back and signed the log with his right hand and his fake name. Squinting to read, he noted Raleigh Becket’s name above. In at 8:20, and out at 8:31.

“It’s 8:47,” the guard on the right said, checking a clock Newt could not see.

Newt filled it in accordingly. He resisted the urge to salute facetiously and instead apologized again before heading down the dark hallway. He’d been issued the temporary ID card on a business trip to Langley two years before, and made some alterations to it afterwards. The trip had been disastrous. At least one useful thing had come of it.

With the door closed behind him, Newt pulled out his glasses and put them back on. The stable corridor that stretched before him was long and unlit. Behind the white bars of every stall was a pocket of pitch black. The only light came from the window at the end of the corridor. As he passed stall after empty stall, the uneven boards beneath his feet became temporary plywood, then concrete. Then he was pushing opening the door at the end of the corridor. It creaked like a rusty spring, making him jump.

Then Newt stepped inside and saw it.

✦

In the summer of 1963, both of them were exiled from London. Newt was put on full-time training and workshop duty in East Anglia. Some mania was possessing the service, and they were dispatching ops almost faster than they could train them. The frenzy came from the top, the untraced spasms of Vice Chief Robert Bowen’s anxiety as the Americans closed their net around him. Nobody would understand until much later.

At the Estate, Newt was being reckless. His technical workshops were disorganized and his trainee lectures were barely comprehensible. He drank late into the night on the roof with Caitlin Lightcap, and on later after she went to bed. But his poor job performance did not get him sent home to London, because Victor had asked for him to be kept out of Headquarters for a while.

Hermann, meanwhile, was on foreign assignment for the first time in his career. By day, he was a university adjunct in East Berlin. By night he conducted the analytical side of a dangerous surveillance operation on Wagner Airbase.

Cover was easy, for a German-born academic. By day, Hermann taught one class while Raleigh Becket, a young but capable op, led the surveillance mission on Wagner Airbase. By night, Hermann was the technical help.

All was overseen by case officer Charles Rennie, crooked old hand and war hero. Robert Bowen had discovered Rennie in occupied Paris, already a con artist of impressive repute, glad-handing German soldiers. He was a natural recruit, and he’d never lost his taste for the grift. He and Bowen looked oddly alike, and they used this passing resemblance to their operational advantage—people called them the Twins. After the war, Victor made three, and together, they went to Istanbul.