11Signal Match

NEWT WAS TIRED. Tired of flipping between BBC 1 and BBC 2. Tired of this ugly carpet. Tired of this headache. Tired of the vague dizziness, the distant ringing. It was louder today. Most of all, he was tired of having nothing to do.

He heard footsteps in the hall and looked up. They stopped right outside his door. Cursing, Newt scrambled up, made unsteadily for the closet, and dove inside. He wedged himself into the dark back corner, head spinning. He listened hard, panting, hand cupped around his good ear. Then the footsteps shuffled onward. He heard a squeaky wheel.

It was the housekeeper.

He slumped back against the scratchy spare blankets. False alarm. Of course. Housekeeper. Obviously.

He closed his eyes. The ringing vibrated in his left ear canal.

How did you get here? he asked himself.

You acted stupid, and now you’re acting stupider, answered the voice in his head.

Yeah, he thought. Sounds about right.

Why had he done it? At the time, it had simply seemed the thing to do—the natural next step in the transmitter investigation. He wasn’t sure he regretted it, still, but a new dread was growing as he confronted a consequence not previously considered.

Treason was one thing. But he was starting to consider that this incident might have been bona fide professional suicide.

If Hermann couldn’t prove he was being framed—which was tough, when he was 100% guilty—he was, at the least, probably going to lose his job.

And why? What for? Why throw a stick of dynamite into the works of a 20-year engineering career? He thought of the Langley incident.

Newt took off his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose, closing his eyes. Solitary confinement was going to drive him crazy.

He crawled out of the closet and got back on his feet. He rubbed his rug-burned hands together, then made his way to the phone. He dialed Caitlin Lightcap’s work number.

The phone stopped mid-ring and a voice said “Lightcap.”

“Yello.”

“Hey kid,” she said, voice warming. “How’ve you been?”

Newt flopped back on the bedspread and looked up at the ceiling. “Oh, me? Never mind about me. How are you, chum?”

“Just peachy, pal,” she said.

“Tell me about your day.”

“Same old,” she said, and he heard the sound of a hole puncher. “We still on for tonight?”

“Tonight?” He groaned. “Oh, shit. It’s Tuesday.”

“You forget what day of the week it is?”

Newt was rubbing his eyes, frustrated. “No—yes—God dammit.”

They had band practice tonight. He'd forgotten completely. And he couldn’t go, because he was in hotel prison. Newt hated letting the girls down—especially Caitlin. The band was one of the few bright spots in her life.

He heard her sigh angrily on the other end. “Well, yes. The rumors are true. It is Tuesday. And we have practice.”

Newt said nothing.

“Right?”

“Right...”

“Look, man, if you’re canceling on me, just say so.”

“No, no—” Newt winced, feeling the full weight of his obligation to her. “Yeah, I’m really, really sorry, but I won’t be able to make it...”

There was a long silence on the line. Newt’s dread grew with every second.

“Man—I’m sorry,” he said, overwhelmed with the feeling that he let everyone down, everyone in his life, without fail. “Really, it’s just that some stuff has come up, and I can’t really get out right now... I’m sorry, I’ll make it up to you, I just—”

There was a sound as she stopped sucking her teeth.

“Lightcap?”

“Yeah?”

Her voice was still tense.

“Can you do me a favor?”

“A favor?”

“Can I borrow a guitar?”

“A guitar? What’s wrong with yours?”

“For practice.”

“Did your goddamn house burn down? Is that what’s going on?”

“Ha—no. No, I kind of wish, but no, I just need to...”

Some chord in his disappointed laugh tipped her off. Her voice turned on a dime.

“Need to what? I’ll bring it over. The guitar. No problem. Just tell me where.”

He gave the name of the hotel. “Room 237. Just leave it at the reception desk.”

“All right. I will. Should I cancel the gig tomorrow?”

“Maybe,” Newt said sadly. “Well, maybe not. I don’t know. Do you mind singing?”

“If you don’t show up? I can manage. Up to you, really.”

Newt chewed his lip.

“I’ll call you.”

“All right.”

“I want to come. I’ll try to come. We should... talk.”

“Ominous.”

Newt said nothing.

“I’ll drop the guitar off after work,” she said. “Don’t scratch on it.”

“I won’t.”

“And don’t do anything weird with it.”

“Weird? Me?”

“I’ll tell Laurie and Vivian. We’ll see you tomorrow. Or maybe not.”

“Thanks. You’re the best.”

“I know. Take it easy, kid.”

“Bye.”

Caitlin rang off, and Newt listened to the dial tone for another moment before hanging up too.

“Newton, where in God’s name did you get that?”

Newt stopped strumming the guitar. The door to their room closed behind Hermann with an ominous click.

“Good afternoon to you too,” Newt said, not turning as Hermann came in. “Or is it evening? I’ve lost track of the time.”

“I told you not to leave this room,” Hermann said to Newt’s back, as Newt sighed and closed his eyes. He heard no sound of Hermann taking his jacket off or putting his bag down. That meant he wanted a fight. “I know you don’t take threats to your safety seriously, but I do, and if you don’t—”

“Hermann! I didn’t leave the damn room, all right?” Newt said, setting the guitar down with a hollow twang. “I had it delivered. Will you settle down?”

“Delivered by whom?”

“Caitlin! She brought it over, left it at the desk, and then someone brought it up to the room. I’ve been in here. All day. Nobody has laid eyes on my precious face. How exactly do you plan on covertly changing hotels? Will we be schlepping through secret tunnels, Dr. Gottlieb?”

Hermann closed his eyes and sighed through his nose, dropping his briefcase onto the carpet. “Yes. We’re going. I’ve booked the rooms. Collect your things. I’ll call a cab.”

He went into the bathroom and shut the door. Newt heard the tap turn on.

“It’s boring as shit being in hiding, you know that, Hermann?” Newt said to the closed door. “And you know, I was actually looking forward to finally talking to someone, after being by myself all day. And instead what I get is scolded. I had absolutely nothing to do until Cait dr—”

The door reopened.

“The walls here are extremely thin,” said Hermann with condescending evenness. “I could hear you playing from the lift. I suggest you quiet down.”

Newt sighed frustratedly and stood up. He put the guitar into its hard-backed case and shut it with excessive force. He dropped his arms to his sides.

“There. Packed.”

Hermann spared him a glance, infuriatingly blank, and went to the phone to call down to the concierge for a taxi. Newt stalked into the bathroom and retrieved their toothbrushes.

A short, silent cab ride brought them to their new temporary home, a tall, bland hotel with a prefabricated lobby full of hideously colored mid-century seating. The rooms themselves were less offensive, carpeted and upholstered in various shades of gunmetal gray. They had a connected pair of rooms, better appointed than the single room they’d left: each had a full-size bed, a sofa, a television, a radio, an A/C unit, a desk with an anglepoise lamp, and wide windows overlooking the busy street. It was a clear, cool day; the sun had sunk behind buildings already, leaving an empty blue sky.

Newt could tell that Hermann’s investigations today had gone poorly, but Hermann refused to explain anything until Newt had searched the new room for listening devices. While he did so, Hermann unpacked the sparse luggage he had bought—a few changes of clothes, razors, soap.

“All clear?” Hermann asked when Newt returned from the adjoining room.

“Yeah,” Newt said. He frowned at the clothes Hermann had bought for him, still packed into the bag on his bed. Did Hermann want him take his things into the other bedroom?

“What? You disapprove of my choices?”

“No,” said Newt, unsure if a fight was coming, and ambivalent about starting one. “I mean, probably. But—you had time to pick all this up, but not to go to the bank and get my transmitter?”

Hermann stubbornly avoided Newt’s eyes. “This was more important,” he said.

Newt sighed.

“Do you want me to take my stuff into the other room and sleep there?” he finally asked.

“What?”

Newt frowned at Hermann.

“No—I only booked two rooms for—appearances. Of course not.”

Mollified, Newt nodded. Hermann felt a stab of guilt for giving Newt such a cold shoulder. Hermann sat down at the desk, leaning his cane against it, and looked at the couch. Newt sat down on top of the desk.

“I think Victor is right,” Hermann said. “I think there’s a mole in the Division.”

Hermann told him what he’d learned—or, for the most part, not learned—in the office that day.

“So you think someone scrubbed Birch’s file, and the 2TP from the British defector,” Newt said. “The same person.”

“Yes,” said Hermann.

“A mole.”

“Yes.”

“It could be institutional,” Newt pointed out. “Birch was a scandal. All that was patched up. The missing file could just be another patch.”

Hermann shook his head. “He knew about Greenwich. Stella said—”

“Yeah, yeah. I guess.”

“And what about the 2TP? What reason would the fifth floor have to hide that?”

“The Greenwich connection?” Newt suggested.

Hermann shook his head. “There’s something else in that message.”

Newt was still frowning, unconvinced.

“How are you feeling?” Hermann asked into the silence. “How’s your ear?”

“Ear? It’s all right,” Newt lied. The ringing was worse, but it was nothing to worry about. He didn’t want to set all Hermann’s crazy alarm bells off.

“Are you still dizzy?”

“Off and on.”

“Is it worse?”

“About the same,” Newt said with persistent optimism.

Hermann frowned and looked away out the window, at the high-rise across the street. Its many windows were reflecting the setting sun. Newt leaned back, hugging one of his knees.

“I want to know who that British source is,” Hermann said, half to himself. “I want to know who sold them the transmitter. I wanted that 2TP message. I wanted to decipher it.”

Newt glanced at him.

“What about asking me?”

Hermann looked at Newt. “Asking you what?”

“For the transmission.”

Hermann stared at him.

Newt raised his eyebrows.

“Do you remember it?” Hermann said in shock.

“Yes,” said Newt, like Hermann was the densest person he’d ever met. “Obviously!”

“And when exactly were you planning on telling me—?”

“Oh my god, Hermann, just give me the notepad.” He stood up and tugged Hermann’s arm. Hermann surrendered the desk chair. “Of course I remember it. Hello? Human Xerox? How can you forget this so often, Hermann, my god. You don’t even care about my stupendous brain. You only love me for my body.”

Hermann watched in amazement as Newt closed his eyes and began to scribble letters in groups of five onto the notepad, his hand moving feverishly.

“The groups don’t actually...”

“Shut up.”

“...matter,” Hermann finished. “And did you see the original matched transmission as well?”

“Yes, yes,” said Newt, tearing a page off and continuing on the next. “It was from September 1950.”

Hermann watched him fill a third, and then a fourth page.

“Done,” said Newt. “And the match...” He began transcribing the matching message.

“Newton,” said Hermann. “Are you in the habit of memorizing all the OTP transmissions that the Blueberry processes?”

“Everyone’s got a hobby,” Newt said, still writing. “No—I mean, yes. Only the matches. I usually take a look.”

“Why on Earth do you do that?”

“Are you seriously complaining about it right now?”

Hermann opened his mouth to retort. Again, it occurred to him how much sensitive information was stored inside of Newton’s head. Nobody at the Division had any idea how much. Not even Hermann.

A few minutes later, Newt tore the last page off triumphantly. He put both packets together and handed them up to Hermann. “Done,” he said. “Can you do anything with these? Or do you need to take them to your buddy Stella?”

Hermann looked offended. “I may be a bit rusty, but I can still handle a matched set of Vigenère ciphers, I should think.”

“They’re OTP, Hermann. There’s no key.”

“Yes, there is. It’s just long. But when you have two messages, it isn’t difficult. It just takes a bit of time.”

“Fine, then, if you’re so smart.” Newt stood up to offer the chair, then grabbed the edge of the desk. “Oy—too fast.”

Hermann steadied his arm. “Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” Newt said, opening his eyes. “I’m fine. Sit. Decode.”

Hermann sat. “Decipher,” he corrected, putting on his glasses.

Newt rolled his eyes and sat back on the couch. Hermann leaned intently over the messages. “And the first message—do you remember where it came from?”

“Hamburg. Embassy message, I think.”

“Lucky,” Hermann muttered. So both messages were in German. He squinted, then took off his glasses and cleaned them with his tie. It had been a while since he’d done an OTP by hand. He put his glasses back on and started writing out a Vigenère Square.

In the long, underhanded history of cryptography, an uncrackable cipher is the holy grail. Many have tried to invent a cipher that can only be read by the sender and the recipient. The onetime pad system is, in a vacuum, that cipher. It cannot be deciphered.

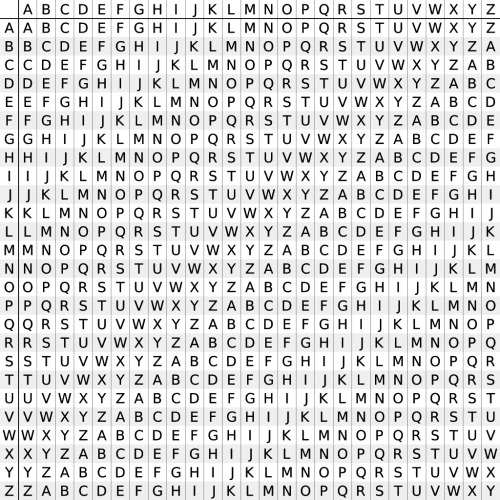

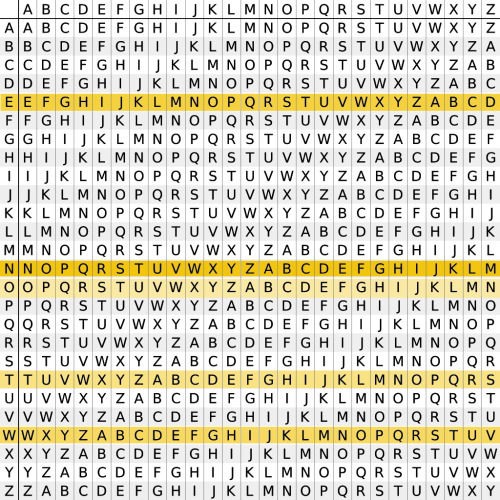

The OTP is descended from the Vigenère Cipher, a fairly secure form of enciphering. The cipher is created using a Vigenère Square, a grid of 26 alphabets resembling a multiplication table. The first alphabet starts with A (A=a, B=b, C=c... Z=z), the second with B, (B=a, C=b, D=c... A=z) and so on, until Z (Z=a, A=b, B=c...Y=z). The completed table is a list of all possible Caesar cipher keys.

Each letter of the message is encoded according to a ‘key,’ a prearranged word. Each letter of this key corresponds to a line in the Vigenère Square. So, in an enciphered message, the first letter of the message corresponds to the first letter of the keyword: if the keyword is, say, “NEWTON,” the sender encodes the first letter according the “N” alphabet, the second in the “E” alphabet, and so on. They repeat the keyword as many times as necessary.

Because each character is encoded from a different alphabet, the cipher is extremely difficult to decrypt. But not impossible. The repetition of the keyword is what makes it vulnerable. A clever cryptanalyst can discover the length of the keyword, and then analyze the frequency of letters in the message to unravel its meaning.

The onetime pad solves that weakness: instead of a repeating key, the key is the same length as the message. And the key itself is a completely random set of letters. This random set of letters is distributed on a pad of paper to only two people. They can then exchange completely secure messages, only to one another, only using each key once. Each letter is encoded on a random line of the Vigenère Square, and the interceptor is never the wiser. It is really, truly unbreakable.

Unless the same key is used more than once.

Perfect cryptographical methods may exist, but perfect organizations do not. The Razvedka’s accidental duplicate set of keypads made a subset of their messages vulnerable to attack. It was this weakness that Newt and Hermann’s Blueberry computer exploited. But Hermann didn’t need a computer to decipher two messages that matched. All he needed was a Vigenère Square.

Hermann was familiarizing himself with the two messages, planning his strategy. Now, they were just a patternless set of letters. But soon, he would pry them apart.

He started with a crib. A crib is a word the analyst assumes to be present in the ciphertext—usually a common word, like “the,” or a name, or a day of the week.

Hermann knew that this message was in German, and he knew when it was sent, so it probably contained the German word for August (August). The first letter of the ciphertext was “N.” Assuming that this represented “A,” that meant that it corresponded to the “N” alphabet. He repeated this with the next three letters, acting as though they spelled out “AUG.” Then he turned his attention to the first message. The two messages shared a random key; assuming that his crib was correct, then he knew the first three alphabets in that key: N, P, E. So he tried the first three letters of the ciphertext according to his key. They revealed “BSO.” Probably not correct. He started over. Assume that “August” starts at the second letter...

Newt lay on the couch, staring at nothing, listening to the scratching of Hermann’s pen. After a few moments he heard another crossing-out, and heard Hermann sigh to himself. He turned to look up. He was staring at the messages with a blank focus Newt recognized. He saw a less intense rendition of it every Sunday over the crossword. It was the total focus of the puzzlemaster. The hotel would have to catch fire or collapse before Hermann took notice.

So Newt got up and took the guitar into the other room to practice. As he was closing the door between their rooms, Hermann said:

“You can leave it open.”

Newt paused.

“The door?”

“Yes. If you’re going to play.”

Newt smiled. “Sure.”

An hour or so later, Newt was hungry. He didn’t hear anything from the other room, so he set the guitar down, took the notepad from his desk, and checked on Hermann.

His partner was standing in front of the window, stretching. The desk was entirely covered in papers, filled to the margins with numbers and letters.

“Hey,” said Newt, approaching with his notepad. “Thought you might need a spare.”

“Thank you. I will soon.” Hermann set it on the desk. “I'm just taking a break.”

“It looks like it’s going well,” Newt said. “Did you find a crib?”

Hermann nodded. “Yes. I have the first few words.”

“Impressive.”

Hermann shrugged modestly, leaning back against the edge of the desk. He began to loosen his tie. “It’s nothing too complex, once you get going.”

Newt smiled wryly. “Right. Nothing too complex.”

Hermann returned his version of a smile, eyes flicking down. “I’ll have it done by morning,” he said.

“But you’re taking a break?” Newt said, moving a little closer. “Right?”

“That’s right.”

“May I?”

Hermann dropped his hands to let Newt take over tie-untying duties. “You’re too kind.”

“The pleasure’s all mine, Dr. Gottlieb,” said Newt. He unknotted the tie, then unbuttoned Hermann's top shirt button, pulled the tie free, and tossed it aside with a flourish that made Hermann laugh. Then he slid his hands under Hermann’s jacket, around his waist, and kissed him.

Newt pushed Hermann back so he sat on the desk. Hermann made some noises of objection as several papers slid off, but Newt kept him quiet. He pushed Hermann’s jacket off and threw it aside onto the couch.

Hermann leaned back for a second of air. Newt secured his position between Hermann’s knees and started playing with the straps of his suspenders.

“You know it’s 1973, right? Not 1913?” he said as Hermann took his glasses off, chain and all, and set them on the desk.

“Braces are more secure,” Hermann said primly.

"You'd wear suspenders and a belt if you could,” Newt said, and nosed under Hermann's chin, pushing the suspenders back off his shoulders. Hermann exhaled.

“Darling—please, watch the papers.”

“What's sexier than a little national security risk?” Newt said, while Hermann ran his hands through Newt’s hair.

“Many—things,” managed Hermann, distracted.

“Mm,” Newt said into his ear, and nipped it.

“Newton...” Hermann said a few minutes and a few buttons later. “I’m not—excuse me—I am not having sex with you on this desk.”

“What?” Newt pulled back. “You’re no fun.”

“You’re an idiot,” said Hermann, too breathless to sound believably annoyed. He gave him a light push on the sternum. “I have work to do.”

Newt scoffed, and kissed him again before letting go. Buttoning up a shirt was much less fun than unbuttoning it, so he let Hermann do it himself. “I’m starving. Maybe human computers don’t need to eat, but engineers do. I’m going downstairs.”

“To the restaurant?” Hermann said, looking up anxiously from his shirt buttons.

“Yes,” said Newt. He took over buttoning. “It’s fine. It’s late. It’ll be empty. And you should eat too.”

Hermann had been successfully put at ease; he acquiesced. They ate in the hotel restaurant. A few solo businessmen were scattered among the tables, eating or drinking alone, and there was one family—two parents with their college-age child, who looked uncomfortable on the verge of adulthood. Newt made charming chatter with the lone waiter. They stuck out like a sore thumb, Hermann knew: they looked incongruous together, uncategorizable as a pair. They would have been safer at odds, or separated. But their familiarity was, by now, impossible to hide.

Hermann watched Newt telling the waiter that, yes, in fact, astronauts could one day grow crops on the moon, and would. Somehow the prefabricated restaurant, with its white tablecloths and chintzy carpet, the mass-production with the gaudy veneer of sophistication, felt too unreal for anything to befall them.

“So, okay. All right,” Newt said, sitting back. He took off his glasses, rubbed his face, ran a hand through his already disorderly hair, and put his palms together. Eyes closed, he said. “So. 1963, UFO crashes.”

Newt opened his eyes, reached across the table, and dragged Hermann’s abandoned plate over. He picked up his untouched bread roll.

“UFO. Crashes in Germany.” He dropped the roll onto the plate. “Abteilung takes it to Wagner. It contains some form of valuable technology. They extract it, do science all over it. Make it a workable input-output. Becket breaks in, steals one part.”

He tore the bun in half and held one half up.

“The transmitter,” Hermann said.

“The transmitter. You go to check it out. It’s gone. Someone has stolen it, hidden it somewhere.” He tucked the ‘transmitter’ half under the rim of the plate. “Transmitter is now MIA.

“Bowen disaster breaks. Some unknown time afterwards, we presume, the USA gets ahold of the output half, the transducer.”

He removed the remaining bread piece from the plate.

“Years go by. The Americans are R&D-ing the transducer. The transmitter is still MIA. Separated, and never the twain shall meet.

“Then in 1971, Abetilung hears from someone in Germany. Brit. This guy’s got the transmitter. Same guy who originally stashed it? Someone who bought it? We don’t know. He—or she—sends an encoded message, reusing the onetime code pad—”

“Cipher.”

“Cipher, whatever, yes, the cipher pad. We intercept their message, process it in the Blueberry in August of 1971.”

Hermann nodded. “Yes.”

Newt retrieved the first piece of bread and put it back onto the plate. “So. He sells the transmitter to the Soviets. Or they steal it from him and imprison him—who knows. Then the Raz call in Tovarish Greenwich. They renew their studies with vigor.

"Then Dr. Greenwich gets cold feet, calls up Becket. Shares his research with the Brits. Becket recognizes the tech from the Wagner mission, and hurries over to get Greenwich's testimony... and his blueprints... and then Greenwich disappears.”

Newt squished the bread up and held it in his right hand.

“Meanwhile,” he said, placing the other half of bread back onto the plate, “the USA brings their completed transducer over to the UK, preparing to bring the two halves together for the first time in ten years. But then some shmuck steals it and gets it stuck in his ear.”

He picked that piece up too, and held it in his left hand.

Both hands out, he looked up at Hermann expectantly. Hermann nodded.

“All correct.”

“So what is it, Hermann? What is it? What does it do?”

“I don’t know.”

Newt opened the ‘transmitter’ half in his fist slowly, and, holding them both out, raised his eyebrows insinuatingly at Hermann.

Hermann caught his meaning.

“We will not find out via trial and error inside your skull.”

“Come on. We have both components. We’re the first people to have both components in ten years.”

Hermann was shaking his head. “Absolutely not. We have no idea what it will do to you.”

“What’s the worst it could do? Kill me? Well do you know what not knowing is doing to me? It’s killing me. I’m dying, Hermann.”

“I’m sure,” said Hermann briskly, sliding his plate back towards himself. “But you’re wrong on one count. We don’t have both components. The transmitter is at the bank.”

“Then get it.”

“And I’m certain the transducer is affecting your hearing,” said Hermann, taking both halves of bread from Newt’s outstretched hands, “because I just said no. Twice.”

Newt dropped his hands into his lap with an annoyed sound as Hermann put them back on his plate and sat back.

“Why won’t you let me test the two components? That transmitter is mine. Technically.”

“I don’t approve of self-experimentation,” said Hermann.

“Well sorry about your principles, Hermann,” said Newt, “but this is the best lead we’ve got, and you know it.”

Hermann looked at him. Why did he feel so reluctant to return Newton’s transmitter to him?

Instead of answering, Hermann picked up half of the torn bread, and ate it.

“You used to flatter me so much,” Newt said, leaning back in his chair. “Back in Menwith Hill. I miss those days.”

“I’m sure you do,” Hermann said.

“You don’t?”

“Not in the slightest.”

“Remember when you sent me that enciphered message?” Newt said in a reminiscent voice. “Without any explanation? That was a risky move.”

“Why? Because the government was reading my mail? Or because you might not be up to breaking it?”

“No. It was just a bit of a move, that’s all,” Newt said, grinning.

“You had written that you enjoyed my puzzles. It was simply...”

“Yes, I know what I wrote!”

Hermann’s cheeks were pink. “Yes, well. When you did decipher it, it was quite tame.”

“I had to go upstairs and get a lesson from the coding bay.”

“I appreciated your commitment to the question.”

“Newt Geiszler: committed to the question 'til they commit me to the institution.”

Hermann took a sip of his drink, his eyes smiling.

“Still, I prefer just doing the crossword together,” said Newt.

Hermann set his glass down. “So do I. It is a great relief to no longer have to scan the Entertainment section of the newspaper to keep up with questions about the music of the Beatles.”

“Glad to help purge that knowledge from your mind. It can live in mine forever. By the way, how many of them are there?”

“How many what?”

“Beatles.”

Hermann thought about it. “Between 3 and 6.”

Conversation wandered to linguistics. Twenty minutes later their waiter interrupted a heated discussion about the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis to tell them the restaurant was closing.

“Your bandmate Laurie is a bad influence,” Hermann said as they got into the lift. Laurie, the drummer, was a linguistics professor by day. Once, she had given Newt an informal lesson on syntax trees; Newt’s subsequent attempt to share that knowledge with Hermann had led to such a broigus that any mention of syntax trees was still banned in Hermann’s apartment.

Newt took Hermann’s arm, closing his eyes as the elevator moved upwards. “Why don’t you show me color terminology that...”

“Yes? That what?”

“Speaking of Laurie,” Newt said, abruptly conversational. “Gig tomorrow.” His eyes were still closed.

The elevator dinged. “That’s a shame,” Hermann said.

“Right. Yeah,” said Newt. “Probably too dangerous.”

“Definitely too dangerous,” said Hermann, leading him out of the lift and back to their rooms. Newt's heart sank

Hermann found a classical station on the wireless and then resumed working. The messages would only reveal themselves through their connections: He had to guess each word of one correctly before he could decipher the next word from the other. It was like doing a crossword puzzle without any hints.

The A/C unit was climatizing aggressively, so Newt dragged the blanket off the bed and curled up on the couch. He was soon asleep. Hermann worked steadily, facing his dim reflection in the wide black glass, vague against the dim city lights. Bach played, Newton snored lightly, and he kept working.

It was well past 2 AM by the time he finished, and Newt was fast asleep. The radio was still playing quietly. But at the slight sound of Hermann setting his pen down, Newt’s snoring cut off.

“You got it?” he said blearily.

He twisted so he could look up. Hermann was rereading what he had deciphered.

“What is this, Gregorian monk music?” Newt mumbled. He stood, unsteady with sleep, and went to look over Hermann’s shoulder. The words were in German and did not resolve immediately to his eye, but he was duly impressed. He kissed Hermann on the temple. “You’re brilliant.”

“Newton.”

Something had emptied out of Hermann’s voice.

“What?”

“The British source. In 1971, the Abteilung picked him up after he woke from a coma. He says he has the transmitter, but he asks to talk to Robert Bowen first. And they want special radio equipment for him—mono input headphones. Because he’s deaf in one ear.”

Hermann looked up at Newt.

“It’s Charles Rennie. He’s alive.”